The Drag Racing Starting Tree or Christmass Tree

Has at its top 4 Round yellow bulbs that warn you when you are getting close to the starting line and the “staged” (ready to race) position. This is called the Pre-Stage area.

Staged Indicator Lights

A second set of round yellow bulbs that tell you when you are on the starting line and ready to race. This is the Staged area. The bulbs light up when the front wheels of the car cross a beam of light that goes to a set of photo cells. These cells trigger the timer when the car leaves the light beam.

Countdown Lights

Round amber floodlights that count down to the green “go” light. There are two types of countdowns or starts. The pro start flashes all three lights simultaneously, with a .400 second difference between the amber and green lights. This is called a Pro or .400 Tree. The bracket starts flashing one light at a time, with a .500 second difference between the last amber and the green light. This is known as a .500 or Sportsman Tree.

Green Light

This is the one you’re waiting for. When the green light flashes, it means you’re free to mash the gas pedal and make a run. This is called the launch.

Red Light

If this bottom bulb flashes, you’re out. The red light will go off when you leave the starting line before the green light is activated, resulting in a disqualification. Known as “redlighting”, this action automatically gives the win to your opponent. Most drivers try to begin their launch just as the last of the three amber lights goes off. That puts the car in motion when the green light activates. This is where most bracket races are won or lost, so time practicing your staging and launching techniques is time well spent.

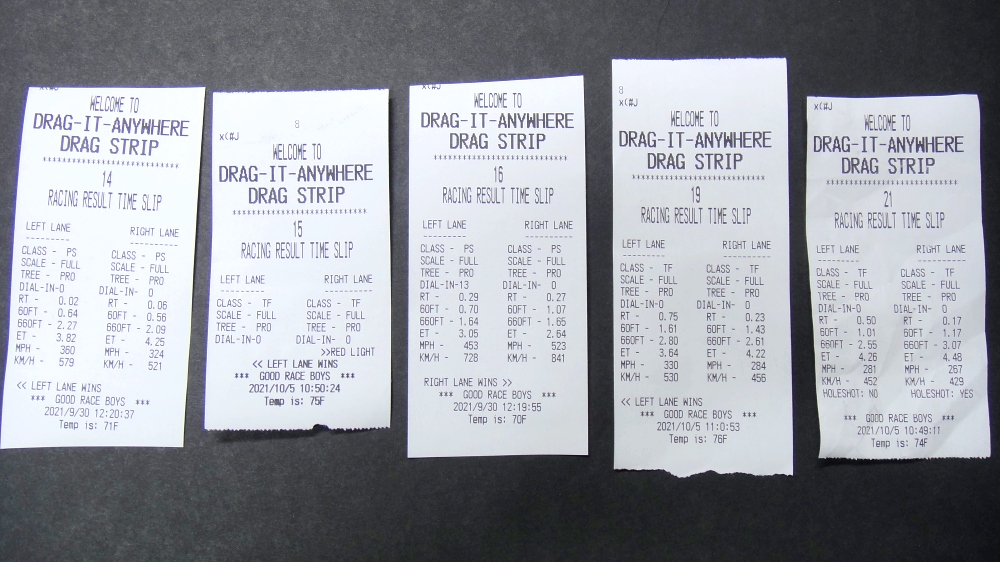

Timeslip

After you make a run, the officials in the little booth at the end of the track will hand you a piece of paper with numbers all over it. This paper is called the timeslip.

When you don’t have a quarter-mile track at your disposal, there is a way to guestimate what your vehicle would run in the 1320 based on its eighth-mile elapsed time. Simply take your eighth-mile time and multiply it by 1.57. For example: a 7.70-second eighth-mile means you’ve got a vehicle capable of going 12.0 in the quarter-mile. In some instances a conversion factor of 1.56 is more accurate, but either one will get you pretty close. Should your quarter-mile timeslip not display your eighth-mile elapsed time for whatever reason, you can simply divide your quarter-mile E.T. by 1.56 or 1.57 to get an accurate idea of what it was.

Just like for E.T., there is a way to accurately deduce what your quarter-mile trap speed would be based on the eighth-mile info you’ve gathered. For a lot of vehicles, multiplying eighth-mile trap speed by a factor of 1.25, 1.26 or sometimes even 1.27 yields great results. Full disclosure: the 1.25 and 1.26 conversion factors suffice most of the time for street-driven diesel trucks participating in drag racing, which is what yours truly spends most of his time at the track indulging in. Aerodynamics definitely play a role here, too, especially on 7,000 to 8,000-pound trucks during the course of a quarter-mile race

On the DIA system Time Slip, our 1/8 mile is the 1000ft Print out. The timeslip provides a wealth of information about a run. It tells you how well you launched, how quick and fast you went at various points on the track, and what your final ET and mile per hour were. And if you were racing against an opponent, the timeslip tells you how they did. The DIA system allows for this with our Thermal printer Ad-On. With this information you can have a recorde of your race as well as see the performance of your cars actions and speed.

Car Number

Most cars are assigned numbers at official races.

Class

Marked if running in an official race. Not used for “test and tune” sessions.

Dial-In

This is the elapsed time you think your car will run.

Reaction Time

This tells you how quickly you reacted to the green light on the Christmas Tree. In this case, it is set as a .500 second or PRO Tree. You want your RT to be at or as close to .500 as possible. If you react faster than that, you’ve just redlighted.

60, 330, 1/8, MPH, and 1000 ET and MPH Times

These figures give you the elapsed times at the 60 foot, 330 foot, 660 foot or eighth-mile, and 1,000 foot marks. You also get the mile per hour figure at the 660 foot mark and MPH Quarter-Mile ET and MPH These are your finishing elapsed time and mile per hour numbers. When it comes to bragging rights, these are the ones that count!

Holeshot In a heads-up (even start) race that would be where the winning car had a slower Elapsed Time than the losing car. This occurs when the winning car and driver leave the starting line sooner then the losing car and even though it took longer to reach the finish line (from the time it left the start to the time it reached the finish) it got there first and won as a result of the better start. In a handicap (uneven start) race such as a bracket race, the same thing occurs additionally taking into account the differences between the handicap times (or dial-ins) and the actual Elapsed Times: The time between the green light coming on (the GO signal) and the car actually leaving the starting line is called the “Reaction Time” and most tracks measure this and supply the information to the driver at the conclusion of the race, on an “Elapsed Time slip” or “ET slip” (the info is printed on a slip of paper). If a driver looks at the results, and sees that he won even with a slower Elapsed Time, he will also see that he had a shorter reaction time. If the difference between 2 drivers’ Reaction Times is greater than the difference between their Elapsed Times, the winning driver can claim that he had a “Hole-Shot Win”. He won because he had a better Reaction Time even though his car was “slower”… By the way: The expression used to explain why the losing (although “faster”) car lost is “He got Treed.” For instance you can say: “I treed that duck with a hole shot…”Awesome! For a wonderful explanation on time slips also SEE THIS PAGE

If you purchase the DIA System and a Thermal Printer you can print out your Race Results and check your RT, Speed ET and more. The example Below shows how it will print out if you select PRINT (POWER BUTTON) on the DIA system. Race #15 Shows a RED LIGHT scenario and Race #21 Shows a HOLESHOT WINNER.

Eagle-eyed reader David Leighton, whose family for years ran California’s Inyokern Dragstrip, pointed out an error in my recent column concerning NHRA’s 1970 switch to a “Pro Start” system at that year’s Supernationals at Ontario Motor Speedway.

In moving away from the five-amber countdown that, in retrospect, must have made life difficult for Top Fuel and Funny Car drivers, to a single-sequence start, I said that all five amber’s flashed simultaneously, which, as Leighton pointed out, was incorrect. “Actually, only the fifth amber light was used,” he noted. “It wasn’t until the Tree was shortened to three amber’s that the Pro Start was expanded to three amber’s at once. Admittedly I do not remember when that took place, but another lost day in the archives could surely turn that up, too.”

How could I turn down a challenge like that? And, this being Christmas time and all, why not a deeper look back at the Tree?

Any drag racing history buff worth his or her Wynn’s Winder decal probably knows that the Tree made its official NHRA debut at the 1963 Nationals in Indy, where Don Garlits famously red-lighted away the Top Eliminator to unheralded Bobby Vodnik, who had “Big” covered by about a tenth going into the final.

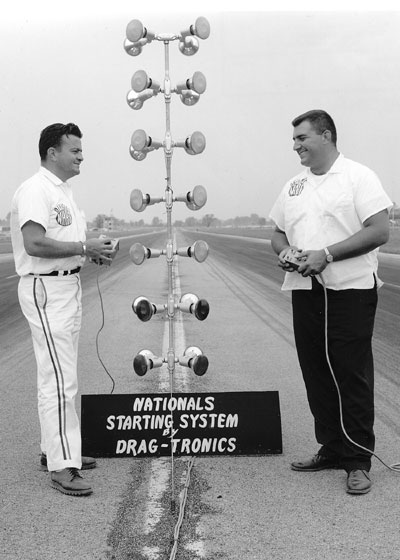

Acrobatic flag starters were entertaining but human, and gave way at the 1963 Nationals to the Countdown Starter. Pictured at that event are Ed Eaton, left, NHRA’s national field director, and Lou Bond, Division 1 Director, who developed the starting system that became known as the Christmas Tree.

(RightPhoto) Some drivers weren’t really keen on the Tree when it was first introduced. Of course, for years, the colorful and acrobatic “flagman” had signaled the start of each race, but the flag starter system, popular with fans and racers alike, had its flaws. Foul starts were rampant as drivers flinched and left if the starter so much as accidentally blinked his eyes, and each starter had his own unique personality … and his “tells,” as Garlits himself pointed out in his book tales From the Drag Strip: “We had all gotten pretty good at reading the flag starter just by watching his eyes. We could read the muscles in his arms and how they tightened up just before he threw the flag. … The older guys hated it when the Tree came in. We eventually adjusted to it, but we really didn’t want it.” Plus there was talk, at smaller events away from the national limelight, of starter favoritism in sharing a pre-waving signal and outrage when a starter might inadvertently minutely change his normal procedure. Electronics was the answer.

The first NHRA Tree (initially known as the Countdown Starter) was designed by then Division 1 Director Lou Bond, and hyped in pre-Indy issues of National DRAGSTER: “Foolproof in design, the new innovation will be a boon to nervous drivers trying for the big win. … An equal start for all is assured.”

The first Tree was pretty simple, with five amber lights, a red, and a green. There were no “pre-stage” or “stage lights” because, at the time, there was only one beam across the starting line. When the drivers got about a foot from it, the starter would activate the Tree, allowing drivers to pretty much invent the system of “shallow staging” or choose to roll in closer to the beam.

The pre-stage and stage lights and beams weren’t far behind, introduced for the 1964 Winternationals and billed as “the automatic line-up system,” though the pre-stage and stage bulbs weren’t yet actually on the Tree, but rather positioned on the starting line itself.

The bulbs finally were added to the Tree over the next couple of seasons, but it wasn’t until, as noted, the last race of the 1970 season that the Tree went from full to Pro start, with just the bottom of five amber bulbs lighting.

Other than component upgrades, the Tree stayed pretty much intact until the start of the 1986 season, where NHRA unveiled a new, streamlined Tree. It was shorter -– three ambers instead of five — and placed farther out from the starting line. And, yes, Virginia, this was when NHRA also adopted the all-flash amber start.

The logic was part simple math and part in reaction to Pro Stock hood scoop development. Eliminating the two bottom bulbs of a Sportsman countdown saved one second per pairing, which added up significantly through a long day of time trials and qualifying, important back then as lighting systems weren’t all they are today and even a few minutes bought back against impending darkness could mean the difference between a completed event and one interrupted by night.

The all-amber flash was a concession to many drivers, especially in Pro Stock, where they were having trouble seeing the bottom bulb over their hood scoops. There also was the convenience of not having to change focus greatly from the stage bulb to the bottom amber, and, more crucially, the extra bulbs made the start a little more fail-safe should that lone amber burn out or break, an ongoing problem that was also eventually addressed.

The last and most significant change came in 2003, when NHRA switched from incandescent bulbs to light emitting diode (LED) bulbs beginning with the season-opening Winternationals. The biggest knock on the incandescent bulbs was their constant failure due to vibration of the fuel-car exhausts that shattered their fragile filaments. Typically, NHRA was changing out an average of 20 bulbs per race, and with the stakes getting ever higher and the cars ever more complex, the last thing anyone wanted was to have to re-run a race because of a blown light bulb.

The event also gave stats hounds a mild coronary as NHRA switched to a .000 base for reaction times instead of the traditional .400 (the time difference between the amber’s and the green), but the LEDs, more easily seen on bright days, were a boon to the driver’s egos. The average Top Fuel and Funny Car reaction in 2002 was .508 but dipped to .075 and 079, respectively, at the end of 2003, a drop of more than .025-second. The Pro Stock class average dropped from .461 to .034. The Tree has remained basically unchanged since.

So, as you’re enjoying the Christmas Tree in your living room this year, remember that its drag-strip namesake, too, took a lot of growing before it reached prime time.